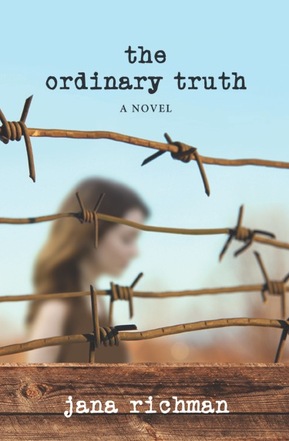

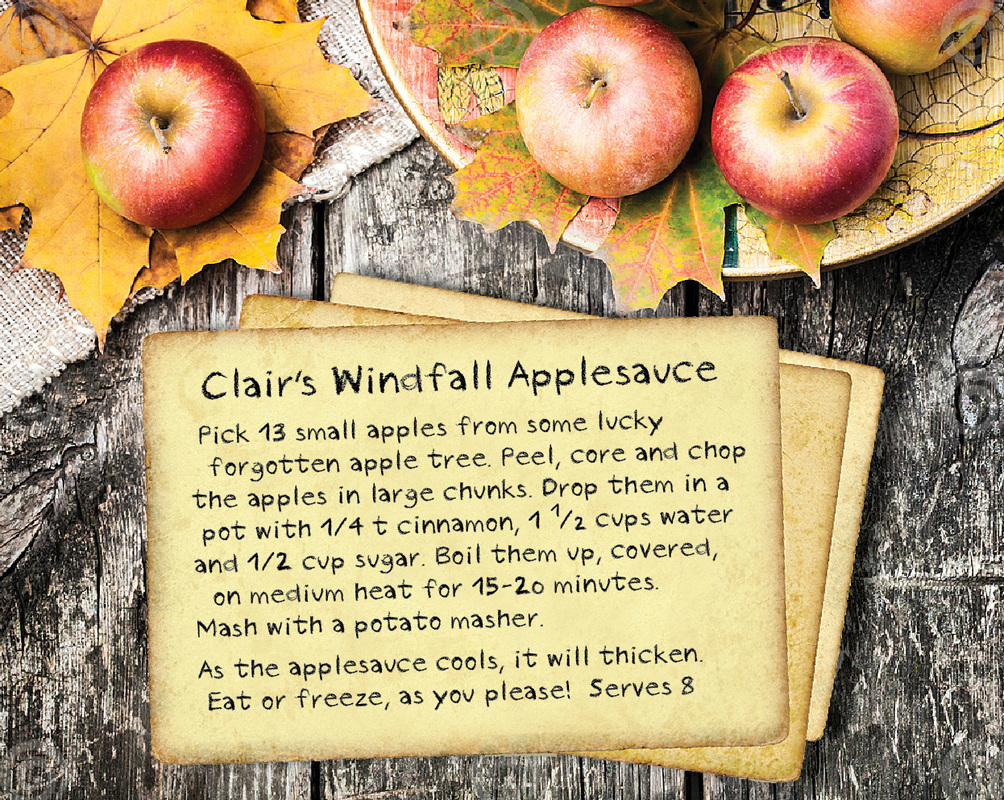

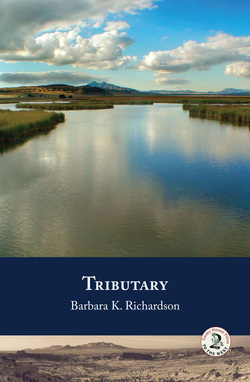

"In her second novel, Barbara K. Richardson brings us in the form of Clair Martin one of the strongest and most complex female characters since Charlotte Bronte gave us Jane Eyre . . .

Read the entire review. The Copperfield Review is devoted to historical fiction.